scroll down for info

This site provides historical insight into the actual characters and events portrayed in Ridley Scott’s film Gladiator. It discusses the film’s plot and ending, so if you have not seen the movie yet, you may want to come back later! I would not want to spoil it for you!

scroll down for text

IS RIDLEY SCOTT’S FILM GLADIATOR A TRUE STORY?

Yes and no.

While it is obvious that an impressive amount of historical and scholarly research was undertaken by the filmmakers, much of the plot is fiction. The fiction does however, appear to be inspired by actual historical events, as will be shown in the appropriate sections below. In this sense, the film is perhaps best seen as a collage, or artistic representation of ancient history, rather than an accurate, chronological, reconstruction of events. While highly original in its own right, the film’s plot does curiously resemble the 1964 film The Fall of the Roman Empire directed by Anthony Mann.

It appears that Scott attempts to present not just a reconstruction of empirical facts, but also to boldly present to us his vision of the culture of ancient Rome, the spirit of its time, and the psychological outlook characteristic of its period. In one word, zeitgeist, and for the psychology of the characters, their mentalite.

It appears that Scott attempts to present not just a reconstruction of empirical facts, but also to boldly present to us his vision of the culture of ancient Rome, the spirit of its time, and the psychological outlook characteristic of its period. In one word, zeitgeist, and for the psychology of the characters, their mentalite.

This area of the film, while imperfect, is still stronger than its actual historical accuracy. Fellini attempted in his own way to do something similarly in his 1969 masterpiece The Satyricon, based on the ancient work by Petronius Arbiter, exploring the psychology of ancient time, in addition to its history. Scott, while historiographically imperfect, due to this creative effort in characterization, is to a certain extent avoiding the anachronisms of psychology present in such films as Spartacus, Cleopatra, and Ben Hur, where the characters appear to think and act solely like modern personages, while wearing unsoiled ancient costumes.

▼ Woodburytype, Jean-Léon Gérôme in his Studio with Large Model of The Gladiators,(1877), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Clearly it would seem, director Scott, and screenwriter David Franzoni, believe that history, at least as they present it, is not a regurgitation of empirical data, but instead an attempt to understand the psychology and culture of its characters, however, the greater purpose of the film is simply to tell a good story. Nevertheless, the film does emphasize Maximus’s worship of his family and ancestors, his obsessive compulsion for virtue and duty, and the stoical elements ever present in his character, which seem to be learned and informed, on the part of those who created this character. The film is inspired by real events, but should, and can not, be taken as an accurate historical source for true events, many of which are known to be different, and with certainty.

WHAT WAS MARCUS AURELIUS REALLY LIKE?

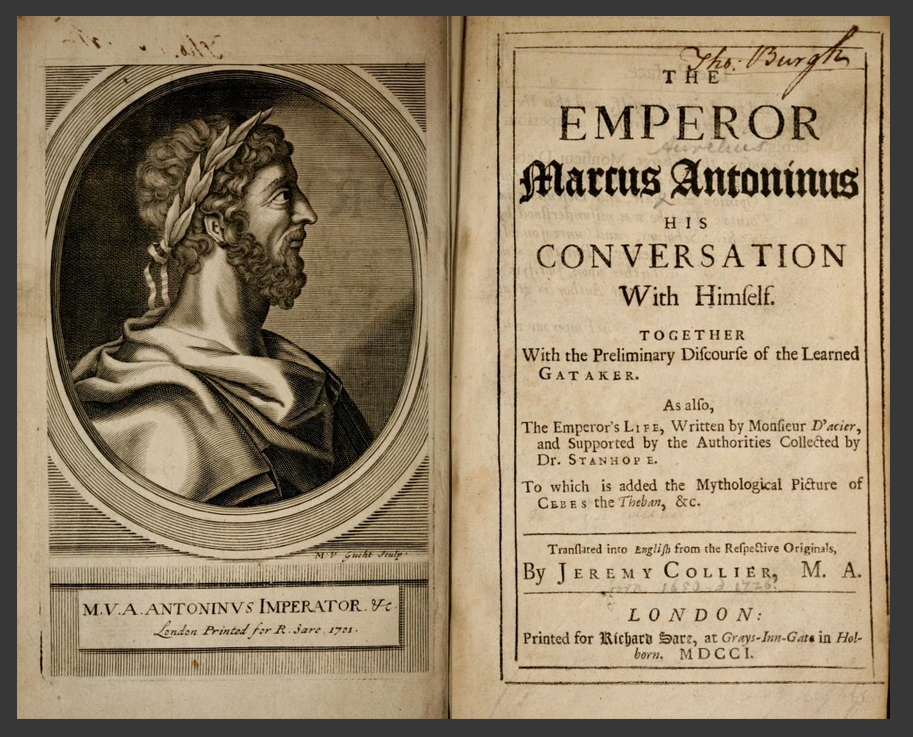

Marcus Aurelius was, as well as emperor from 161 to 180 CE, a stoic philosopher. He  really did wage battles along the frontier as depicted in the film, and is remembered by historians of his time as a competent ruler, whom they favour. His name in full was Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, and these are the titles to which he would have been referred, not the anachronistic “sire” and “my lord” as in the film.

really did wage battles along the frontier as depicted in the film, and is remembered by historians of his time as a competent ruler, whom they favour. His name in full was Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, and these are the titles to which he would have been referred, not the anachronistic “sire” and “my lord” as in the film.

His work The Meditations, although more a compilation of existing stoical thought than a work of great originality, remains a highly readable classic in philosophy.

▼ Title pages from The Emperor Marcus Antoninus : his conversation with himself (The Meditations), Marcus Aurelius, London: (1701), Duke University Libraries.

An interesting fact omitted in the film, was that his adoptive brother and husband to daughter Lucilla, Lucius Verus, was made co-emperor with Marcus. In the time of the Republic, Rome was not ruled by emperors, but rather by two consuls. These consuls, with equal power, were to guard against dictatorship. So, perhaps Marcus really did have Republican inclinations, as attested to in the film, or perhaps this was a Machiavellian maneuver undertaken in an attempt to avoid the fate of the perceived dictator Julius Caesar. This was the first time in history that the Roman Empire had two joint emperors of formally equal constitutional status and powers, although in reality, Marcus was clearly the ruler of Rome.

An interesting fact omitted in the film, was that his adoptive brother and husband to daughter Lucilla, Lucius Verus, was made co-emperor with Marcus. In the time of the Republic, Rome was not ruled by emperors, but rather by two consuls. These consuls, with equal power, were to guard against dictatorship. So, perhaps Marcus really did have Republican inclinations, as attested to in the film, or perhaps this was a Machiavellian maneuver undertaken in an attempt to avoid the fate of the perceived dictator Julius Caesar. This was the first time in history that the Roman Empire had two joint emperors of formally equal constitutional status and powers, although in reality, Marcus was clearly the ruler of Rome.

▼ Bronze bust of Lucius Verus, Roman, (Ca. 170 – 180 CE), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

WHAT WAS COMMODUS REALLY LIKE?

If the ancient sources can be trusted, Commodus was even more bizarre in real life than he was in the film.

Commodus, whose full name was Caesar Marcus Aurelius Commodus Antoninus Augustus, was proclaimed Caesar at age 5 and joint emperor (co-Augustus) at the age of 17, in 177 CE, by his father, Marcus Aurelius. Reality was very different than the film in this instance. Commodus was, as depicted in Gladiator, present with his father during the Danubian wars, and yes, this is where Marcus Aurelius died. As for the actual circumstances of his father’s death, see below.

Historians from the time of Commodus have not been kind to him. As aristocratic intellectuals, they were not amused by his crude antics. Hence, our present day historiography still reflects, rightly or wrongly, this ancient bias. His father, possessing the virtues seen as noble by the literate aristocracy, was, and often still is, regarded as a great man, while his son was hated by the Senate and ridiculed by historians. Yet it is said that the army and the lower classes loved him. Cassius Dio, a senator and historian  who lived during the reign of both Commodus and his father wrote, in regards to the accession of Commodus, that “our history now descends from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust, as affairs did for the Romans of that day.”

who lived during the reign of both Commodus and his father wrote, in regards to the accession of Commodus, that “our history now descends from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust, as affairs did for the Romans of that day.”

▼ Coin of Commodus Ca. 180 CE, Obverse: Laureate Bust of Commodus, facing right, COMMODVS ANT AVG TR P II, Encyclopedia of Roman Imperial Coins.

Indeed, some historians even question his sanity. Commodus, in his own time, was accused of being a megalomaniac. He renamed Rome Colonia Commodiana, the “Colony of Commodus”, and renamed the months of the year after titles held in his honour, namely, Lucius, Aelius, Aurelius, Commodus, Augustus, Herculeus, Romanus, Exsuperatorius, Amazonius, Invictus, Felix, and Pius. The Senate was renamed the Commodian Fortunate Senate, and the Roman people were given the name Commodianus.

Historian Aelius Lampridius tells us that “Commodus lived, rioting in the palace amid banquets and in baths along with 300 concubines, gathered together for their beauty and chosen from both matrons and harlots… By his orders concubines were debauched before his own eyes, and he was not free from the disgrace of intimacy with young men, defiling every part of his body in dealings with persons of either sex.”

Commodus went so far as to declare himself the new founder of Rome, a “new Romulus”. In attempting to boast a new “Golden Age” of Rome, he was clearly emulating his father. But the effect was to make him the laughing stock of the aristocratic class.

DID COMMODUS REALLY KILL HIS FATHER?

Maybe.

Some sources suspect that he did. The fact that he was present at the time, made a hasty peace with the enemy, and a quick retreat back to Rome in a victory triumph, has fueled speculation. The official story is that Marcus Aurelius died of plague.

DID COMMODUS REALLY FIGHT AS A GLADIATOR?

Yes!

In this case, the truth is even stranger than the fiction. Commodus claimed to be descended from the God Hercules, and even began to dress like him, wearing lion skins and carrying a club.

The historian Herodian wrote that “in his gladiatorial combats, he defeated his opponents with ease, and he did no more than wound them, since they all submitted to him, but only because they knew he was the emperor, not because he was truly a gladiator.”

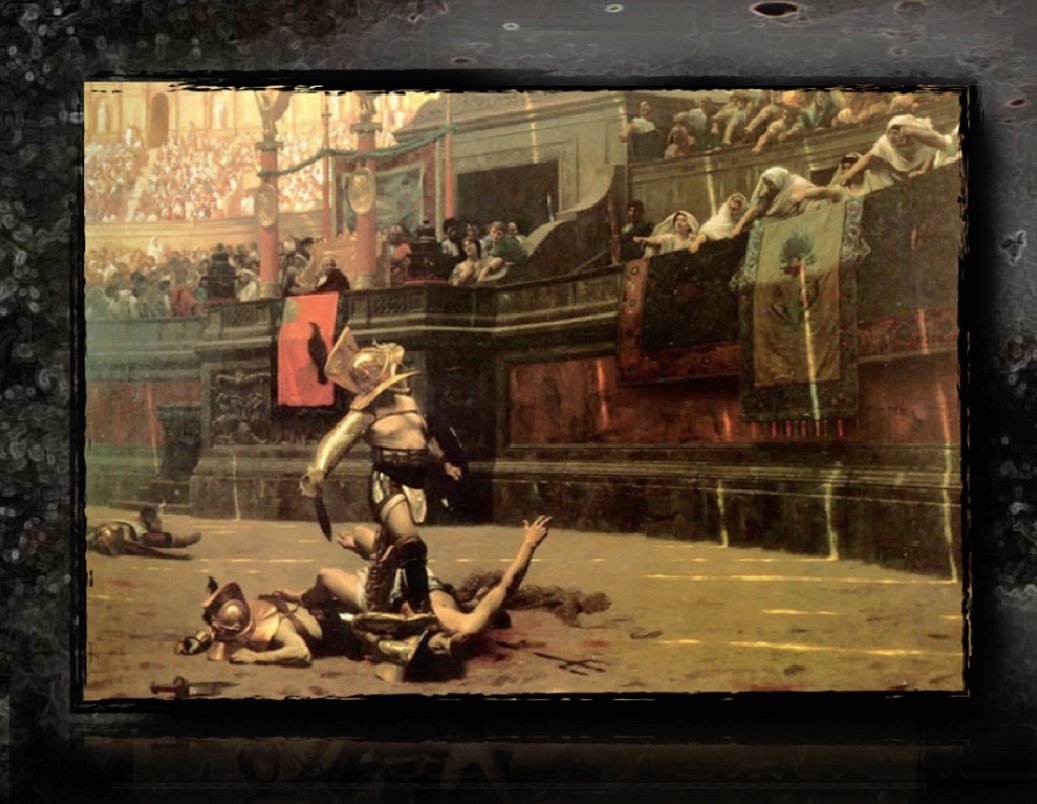

▼ Oil on Canvas, Pollice Verso, Jean-Léon Gérôme, (1872), Phoenix Art Museum.

He also fought wild beasts. Dio Cassius wrote that Commodus killed five hippopotami at one time. He also killed two elephants, several rhinoceroses, and a giraffe “with the greatest of ease”. Herodian tells us further that Commodus had a special platform constructed which encircled the arena, from which he would display his skills as a hunter. He is recorded to have killed one hundred leopards with one hundred javelins. As a theatrical treat, he would slice the heads off of ostriches with crescent-headed arrows, which would then run around the amphitheater headless.

Dio Cassius reveals that Senators were made to attend these spectacles, and that on one occasion Commodus killed an ostrich and displayed the severed head in one hand, his sword dripping with blood in the other, thus implying that he could treat them the same way.

▼ Ippolito Caffi (Italian, 1809 – 1866 ), Interior of the Colosseum, , watercolor and gouache over graphite on wove paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

DID COMMODUS REALLY DIE IN THE ARENA?

No.

However he was assassinated, and, by an athlete. There were numerous plots and attempts upon his life, but the one which finally succeeded was carried out by a wrestler  named Narcissus, while Commodus was in his bath. The plot was orchestrated by his closest advisors, and apparently even included his mistress, Marcia.

named Narcissus, while Commodus was in his bath. The plot was orchestrated by his closest advisors, and apparently even included his mistress, Marcia.

It occurred on the very last day of the year 192 CE, and indeed, exactly when the rest of Rome was preparing festivities for the New Year, 193 CE. However, it was feared and believed by insiders that Commodus planned to kill the consuls-elect, who by both tradition and jurisprudence were to begin their terms upon New Year’s Day, and be sworn in as consul himself, instead. This he reportedly was going to do even outfitted as a gladiator, in his lion skins, with appropriate weapons. This was the final outrage, according to our ancient sources, and thus, his fate was sealed.

▼ Terracotta lamp illustrating gladiators in combat, North Africa, (late 1st – early 2nd century CE), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Commodus ruled for 12 years, a much longer period than alluded to in the film. Dio Cassius wrote that Commodus was “a greater curse to the Romans than any pestilence or any crime.”

WAS THE REPUBLIC RESTORED AFTER THE DEATH OF COMMODUS?

No.

The film is very wrong on this count. A republic is a system of government which does not have a hereditary monarch. An emperor is a monarch. The United States for instance is a republic, and England is not.

Rome was not founded as a republic, as was stated erroneously by a senator, who would have known better, as all educated Romans would hold this as basic knowledge, in the film. Legend has it that Rome was originally ruled by Etruscan kings. The first king was Romulus. The kings were overthrown in a revolution, which was sparked by the rape of Lucretia, in 509 BCE, by Sextus Tarquin, the son of the seventh and last king, Tarquinius Superbus.

Dictators and kings were thereafter despised by Romans, hence, the ideological adulation of a republican system of government, which was a central theme of Roman history, and thus correctly emphasized in the movie, and unlikely by accident, it should be noted.

After Commodus was murdered, the Senate met before daybreak, and declared sixty-six year old Pertinax, who was the son of a former slave, emperor. Pertinax thus became emperor on January 1st, but he was murdered by a group of soldiers the following March, after less than three months in power.

▼ Etching, Rome Ancienne, Jean Daullé, (1759), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

WHAT WAS MAXIMUS REALLY LIKE?

Maximus Decimus Meridius (his full name is stated only once in the film) is a fictitious character!

Although he did not exist, he seems as if he could be be a composite of actual historical figures. In the film, Maximus was Marcus Aurelius’ general. There was in fact a general by the name of Avidius Cassius, who was involved in the military campaign shown in the film, and, upon hearing a rumor of Marcus Aurelius’ death, declared himself emperor. He however, was assassinated by his own soldiers. It is true that there was, in the later Empire, a General by the name of Maximus who appears to have had revolutionary intentions. He is most likely an inspiration as well.

Maximus also reminds one of the emperor Diocletian. Remember that in the film, Marcus Aurelius names Maximus as his heir. Diocletian, who ruled Rome from 284 to 305 CE, was born in the lower classes, like Maximus. He eventually became his emperor’s trusted favourite and bodyguard, and later became a general. Finally he was named heir, and thus became emperor.

trusted favourite and bodyguard, and later became a general. Finally he was named heir, and thus became emperor.

▼ Marble Sculpture, Bust of Emperor Commodus, (Ca. 180 – 185 CE), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Commodus, in reality, was not murdered in the arena by Maximus. He was however murdered by a wrestler. So the character Maximus, while fictitious, is not that far-fetched. He appears credibly, as if he could perhaps be inspired by a collage of other, real, historical figures that have been researched, even if not one himself.

As for his personality, he was definitely a stoic, as evidenced by his sense of obligation to the state, and concern for duty and virtue. This makes sense, given his admiration for Marcus Aurelius, who was a stoic philosopher. One difficulty is, even though many Romans (and not just Christians) believed in an afterlife, stoics usually did not. So this is problematic pertaining to his mentalite in the film, as it is a glaring inconsistency with his other somewhat more correctly presented stoical beliefs .

DID SENATOR GRACCHUS REALLY EXIST?

No.

The ideology which he represents is however, somewhat authentic. Senator Gracchus appears to be based upon Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus. During the Republic, these two brothers, were, one after the other, plebeian tribunes (not senators). They were champions of the common people, and paid the cost with their lives.

Tiberius Gracchus was elected tribune of the people in 133 BCE, and fought for reforms of benefit to the plebeians. He was murdered by opponents. His brother Gaius was elected tribune of the people in 123 BCE, and attempted the continuation of popular reforms. He was also murdered. It is problematic that in the film Gracchus was a senator, in the sense that it was the senatorial class which opposed Gauis and Tiberius, and even participated in their murder.

The political infrastructure of ancient Rome evolved over time, and was actually more complex than portrayed in the film. Other important political entities, along with the Senate, were the Plebeian Tribunate, as well as the Comitia Centuriata. These, along with two Consuls who would rule jointly, are the basic Republican institutions so cherished by Romans, and which emperors would claim to restore.

DID LUCILLA REALLY PLOT AGAINST HER BROTHER?

Yes.

Commodus really did have a sister Lucilla, and she hated her brother. Lucilla was at one time married to Lucius Verus, as her son tells Maximus in the film. What is not said is that Verus was co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius. Lucilla conspired against Commodus, and attempted to have him assassinated in 182 CE. Commodus banished Lucilla to the island of Capreae as punishment, and ordered her execution shortly after. So then, the film portrayal is actually entirely backwards, as Commodus not only outlived Lucilla, he was responsible for her death, and not the other way around, as Hollywood would have it.

Commodus really did have a sister Lucilla, and she hated her brother. Lucilla was at one time married to Lucius Verus, as her son tells Maximus in the film. What is not said is that Verus was co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius. Lucilla conspired against Commodus, and attempted to have him assassinated in 182 CE. Commodus banished Lucilla to the island of Capreae as punishment, and ordered her execution shortly after. So then, the film portrayal is actually entirely backwards, as Commodus not only outlived Lucilla, he was responsible for her death, and not the other way around, as Hollywood would have it.

▼ Coin of Lucilla Ca. 180 CE, Obverse: Bust of Lucilla, facing right, LVCILLA AVGVSTA, Encyclopedia of Roman Imperial Coins.

▼ Coin of Lucilla Ca. 180 CE, Reverse: Juno standing left, raising hand and holding baby, IVNONI LVCINAE, Encyclopedia of Roman Imperial Coins.

Incidentally, ancient historians are not too shy to reveal details, such as it was his other sisters, not Lucilla, that Commodus reputedly enjoyed having degrading sexual relations with.

DID WOMEN REALLY FIGHT IN THE ARENA?

Yes.

Some criticism by film reviewers has been levied towards Scott for having a female gladiator. However, the ancient sources are clear; they did in fact exist. Tacitus, for instance, wrote that Nero staged “a number of gladiatorial shows, equal in magnificence to their predecessors, though more women of rank and senators disgraced themselves in the arena”. Petronius, in The Satyricon, wrote of female charioteers. Dio Cassius explained how some women performed as venatores, that is gladiators who fought wild beasts. The Emperor Domitian staged games in which women battled pygmies.

Some criticism by film reviewers has been levied towards Scott for having a female gladiator. However, the ancient sources are clear; they did in fact exist. Tacitus, for instance, wrote that Nero staged “a number of gladiatorial shows, equal in magnificence to their predecessors, though more women of rank and senators disgraced themselves in the arena”. Petronius, in The Satyricon, wrote of female charioteers. Dio Cassius explained how some women performed as venatores, that is gladiators who fought wild beasts. The Emperor Domitian staged games in which women battled pygmies.

▼ Image of the Roman Colosseum, The Continent by Queenboro’ via Flushing, A handbook for English and American tourists, (1894), The British Library, HMNTS 10097.c.31.

Women were forbidden from gladiatorial performances shortly after the time of Commodus, by the emperor Alexander Severus, in 200 CE.

WHAT’S WITH THE TATTOO WORN BY MAXIMUS?

S.P.Q.R., the letters of the tattoo worn by Maximus, was an abbreviation for an oft used Latin phrase whose English translation is “the Senate and People of Rome”.

The Latin word for “tattoo” was stigma, and our modern meaning of stigmatize, as a pejorative, has clearly evolved from the Latin. It was slaves, gladiators, criminals, and later, soldiers, who were tattooed, as an identifying mark.

The Latin word for “tattoo” was stigma, and our modern meaning of stigmatize, as a pejorative, has clearly evolved from the Latin. It was slaves, gladiators, criminals, and later, soldiers, who were tattooed, as an identifying mark.

Upper class Romans did not partake in tattooing, which they associated with either marginal groups, or foreigners, such as Thracians, who were known to tattoo extensively. The emperor Caligula is said to have forced individuals of rank to become tattooed as an embarrassment.

▼ Image of a Roman Legion’s Standard with SPQR, L’ Algérie Ouvrage Illustré (1885), The British Library, HMNTS 10097.c.31.

In late antiquity, the Roman army consisted largely of mercenaries, they were tattooed in order that deserters could be identified.

The sixth century Roman physician, Aetius, wrote that:

“Stigmates are the marks which are made on the face and other parts of the body. We see such marks on the hands of soldiers. To perform the operation they use ink made according to this formula: Egyptian pine wood (acacia) and especially the bark, one pound; corroded bronze, two ounces; gall, two ounces; vitriol, one ounce. Mix well and sift… First wash the place to be tattooed with leek juice and then prick in the design with pointed needles until blood is drawn. Then rub in the ink.”

such marks on the hands of soldiers. To perform the operation they use ink made according to this formula: Egyptian pine wood (acacia) and especially the bark, one pound; corroded bronze, two ounces; gall, two ounces; vitriol, one ounce. Mix well and sift… First wash the place to be tattooed with leek juice and then prick in the design with pointed needles until blood is drawn. Then rub in the ink.”

The Christian emperor Constantine, ca. 325 CE, decreed that individuals condemned to fight as gladiators or to work in the mines could be tattooed on the legs or the hands, but not on the face, because “the face, which has been formed in the image of the divine beauty, should be defiled as little as possible.”

▼ Engraved Gem, Warrior or Gladiator, European, (Ca. 1750 – 1850 CE), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

In 787, Pope Hadrian the First prohibited tattooing altogether, due to its association with superstition, paganism, and the marginal classes.

© Procopius Canning • Perusine Press • All Rights Reserved • Contact •